Perfecting the CMP Process for Surgical Blades

Planatome’s Keith Jeffcoat shares critical considerations for achieving and consistently producing a nanoscale surface finish that removes jagged serration from conventional blades and ensures a smooth, clean incision.

The scalpel has been the foundation of surgical procedures for more than 1,000 years, according to a recent white-paper from medical device technology company Planatome, but the disposable scalpel blade has been relatively unchanged since its original patent in 1915, despite the evolution of surgical techniques.

While Planatome doesn’t manufacture the scalpel, the Phoenix, Arizona-based company is on a mission to perfect it.

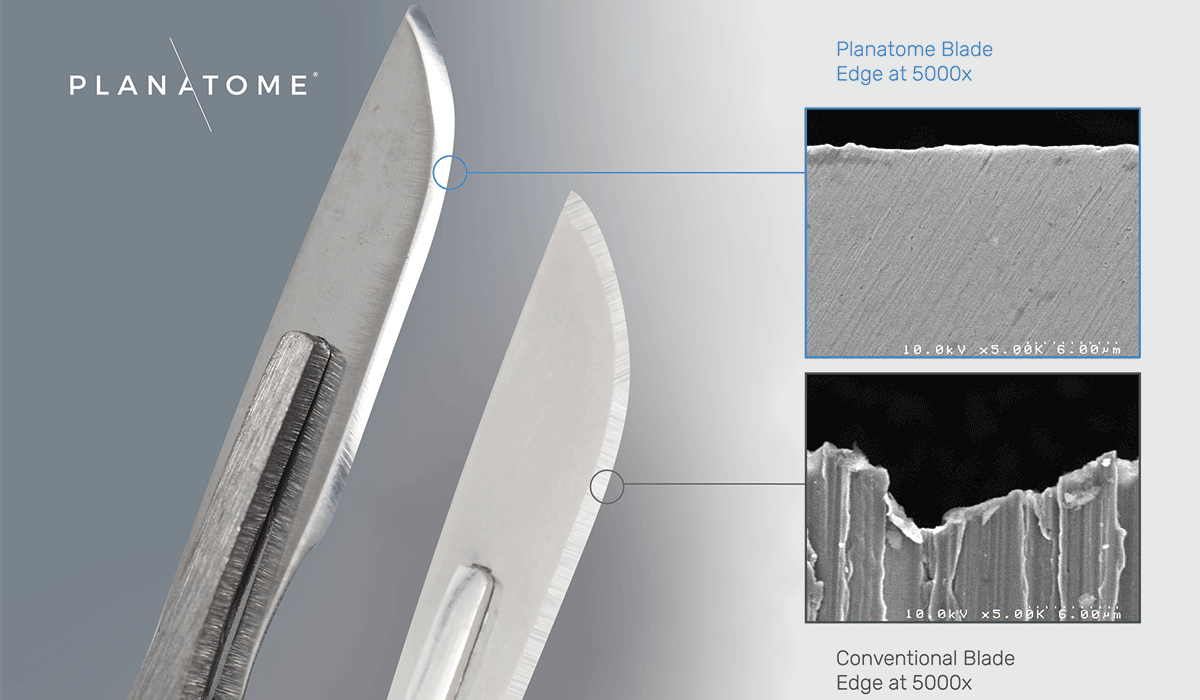

The conventional scalpel blade has inherent defects from the manufacturing process – irregularities in the bevel and edge that can snag, rip, and tear tissue, negatively affecting surgical outcomes with prolonged healing times, worsened cosmetic results, and increased postoperative complications.

Planatome technology removes jagged serration from conventional blades through a finishing step that results in a near molecularly perfect edge and changes the cutting mechanism from a sawing, snagging action to a smooth, clean incision.

Keith Jeffcoat, DEng, MBA, PMP, Chief Technology Officer of Planatome, shares insight into this technology, including the critical considerations for achieving and consistently producing a nanoscale surface finish.

Keith Jeffcoat (KJ): The technology originated from the semiconductor manufacturing industry, specifically a polish process called chemical mechanical planarization (CMP). Developed by IBM in the late 1980s, CMP is a complex but mature and reliable manufacturing technology. Chip makers use CMP to produce an ultra-smooth, near molecularly perfect surface finish, which enables the addition of subsequent layers in the transistors. Planatome LLC was a spin-out from co-founder Tim Tobin’s original company, Entrepix Inc., acquired by Amtech Systems in January 2023. Entrepix was a leader in CMP process technology, developing and providing solutions for companies such as Intel, Apple, and Samsung. Entrepix believed products in other industries could significantly benefit from CMP technology, as well.

The application of CMP outside chip manufacturing is new with the emergence of Planatome, but the chemistry and physics are well understood by subject matter experts from this space. One such expert is the company’s co-founder and inventor of the Planatome technology, Dr. Cliff Spiro, who began developing this application when he was CTO of semiconductor industry CMP materials supplier, Cabot Microelectronics Corp., since acquired by Entegris Inc.

The last major patent for the disposable scalpel was filed in 1915. Spiro hypothesized that an improvement upon the age-old finish of the disposable scalpel may result in better surgical outcomes. That proved to be the case during Entrepix’s evaluation phase. At that point, Planatome was formerly spun off and is now an independently operating company focused on healing benefits and improving the lives of others using this novel technology, initially in the medical industry and subsequently in others as well.

KJ: In the semiconductor industry, an extremely planar mechanical pad, combined with a polishing compound known as slurry, is applied to the chip surface rotating at high speed to produce the ultra-smooth finish. Unlike the semiconductor process, our blade geometry is curved, which increases the difficulty in fixturing and applying the CMP. Blades must be fixed in a way preventing movement and allowing for the precise application of our proprietary fixturing design and CMP process to be applied.

The physical application of specific chemical compounds with mechanical media happens in unison and removes material from the blade. A blade finish can be tailored to the specific clinical application. Upon completion of the polishing, blades are cleaned, packaged, sterilized, and ready for use by surgeons.

KJ: Planatome spent significant time and resources creating the polish process for surgical stainless steel and developing the highly modified equipment to deploy CMP on surgical blades. We use proprietary customized manufacturing equipment to polish the blades precisely to a nanometer-level finish, at least 1,000x more precise and far beyond conventional blades. Without divulging specific details, selecting the proper mechanical media and chemical polishing slurries, as well as precise control of the blade, are key to achieving and consistently producing a nanoscale surface finish.

KJ: In the past century, virtually everything in the medical field has seen tremendous advancements, groundbreaking new devices, therapies, and techniques. Yet the conventional surgical blade is still manufactured as it was in the early 1900s, using diamond grit grinding wheels, producing a highly serrated, jagged edge that saws and tears tissue when it cuts.

Planatome technology removes every jagged serration from conventional blades. This finishing step changes the cutting mechanism from a sawing, snagging action of the conventional blade to a smooth, clean incision eliminating harmful micro-tearing of tissue. This creates low-trauma, high-precision incisions improving clinical outcomes, with faster and more thorough healing, plus reduced swelling, pain, and scarring, which support a lower risk of postoperative complications. The scalpel blade is the most fundamental surgical instrument, and its incision quality sets the foundation for patient healing. Planatome blades make every incision clinically better – and every incision matters.

Although not the original intent of the technology, Planatome blades are also considerably more durable, 5x to 15x more than a conventional blade, which yields additional economic, efficiency, and safety benefits for surgeons and medical facilities.

KJ: Conceptually, Planatome’s technology is very simple – add one finishing step to polish away all the inherent defects of the conventional blade. After that step, only the traditional cleaning, packaging, labeling, and sterilization is required.

Upon understanding the highly intuitive nature of the technology, it’s common for doctors to quickly identify other instruments in their specialty that would benefit from adding this one finishing step – such as bone saws, drill bits, energy devices, and needles.

KJ: The ultimate edge of conventional blades exhibits peak-to-valley surface roughness (Ra) in the 5,000nm to 50,000nm range. This is the same order of magnitude as human tissue cells, whose diameters range from 10,000nm to 100,000nm. This correlation means a conventional blade tears out entire tissue cells connected through the extracellular matrix fibers to as many as 40 cells on each side of the incision. This rips out a wake of excess tissue damage as much as 80 cells wide.

KJ: The Planatome process results in a surface roughness (Ra) in the 5nm to 20nm range, significantly less than the Ra of human tissue, resulting in less damage.

In practice, as shown in porcine abdomen tissue, the actual tissue damage created by a conventional blade is dramatically different from a Planatome blade and is visible even under moderate magnification.

KJ: We perform all CMP of the blades in our Phoenix, Arizona facility. We maintain the highest value-add steps in-house and use contract manufacturing for things with ample external expertise and resources, such as cleaning, packing, and sterilization of the blades. Planatome has patents, issued and pending, but in addition, the company maintains trade secrets it believes are key to safeguarding its technology and competitive advantages.

KJ: While CMP technology can be adapted to virtually any solid material and form factor, we currently buy four types of bulk, non-sterile scalpel blades and apply the Planatome finish to the devices. These four types – #10, #11, #15, and #15c – of disposable surgical blades are well over 95% of all general-use scalpel blades. These devices are single-patient, one-time use in clinical settings. Our process is indifferent to the base supplier and can be applied to blades from any existing medical device manufacturer.

KJ: Planatome’s initial flagship product is the disposable surgical scalpel blade. The process platform for the polished blade lends itself to other surgical devices. The company has defined new products from the platform and plans for the next application of its technology to benefit keratomes (specialty ophthalmic blade) and surgical scissors, including open, laparoscopic, and robotic end-effectors.

From a surgical perspective, the target market is surgeons performing procedures in soft tissue who value superior healing. Planatome expects to expand into many specialties, including plastic, reconstructive, Ob/Gyn, orthopedic, general, and neurology. At Planatome, we believe in improving the lives of others through the delivery of low-trauma surgical instruments. There’s a lot of work to do to fully meet this vision.

About the author: Melissa Schiller is senior editor of Today’s Medical Developments.